Easter is upon us, and while Svalbard is currently entering another cold spell (it is effectively below -30°C here), it has also offered up beautiful misty icy-covered fjords and sunshine pouring into the print studio.

Trial and error

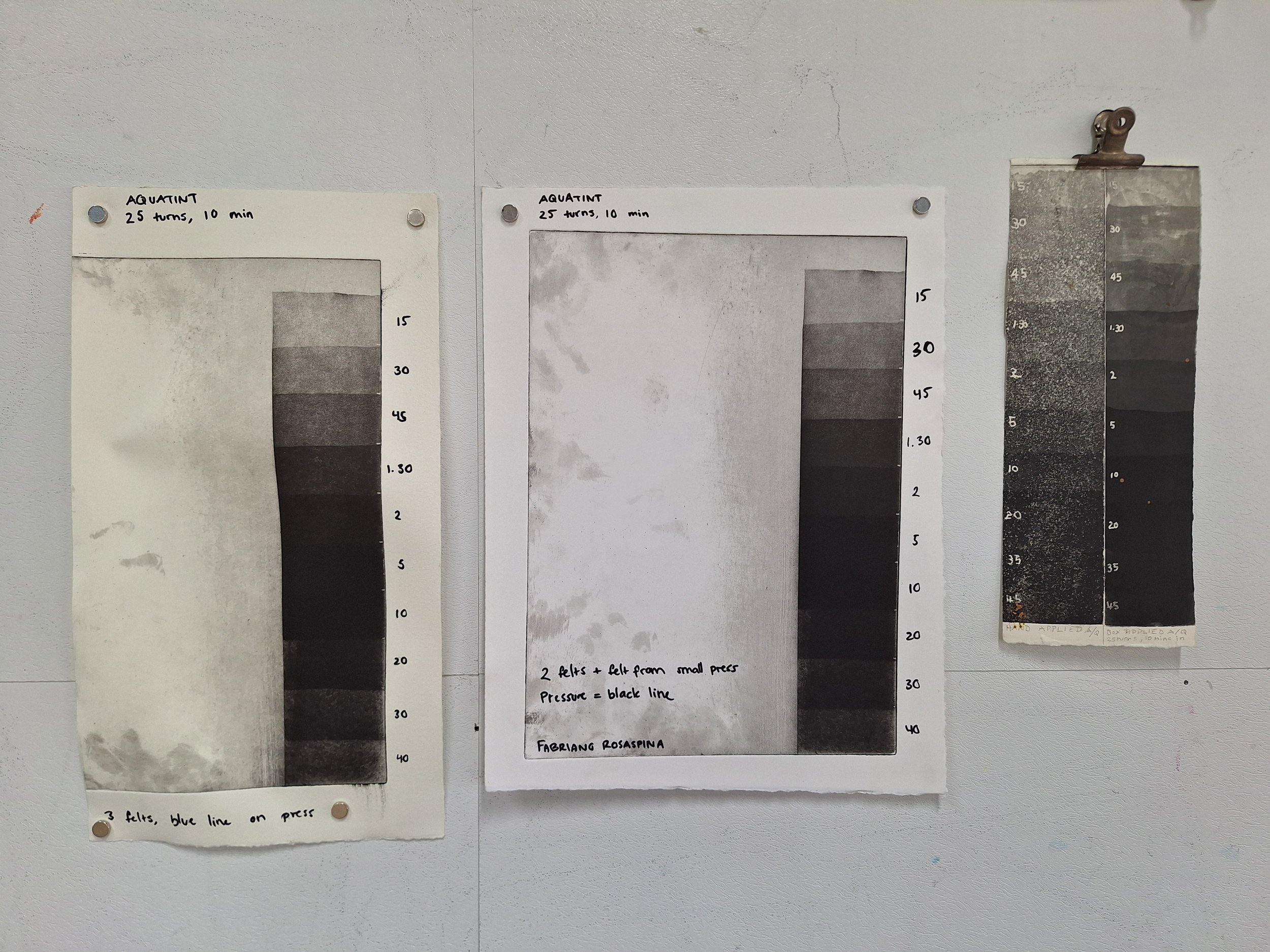

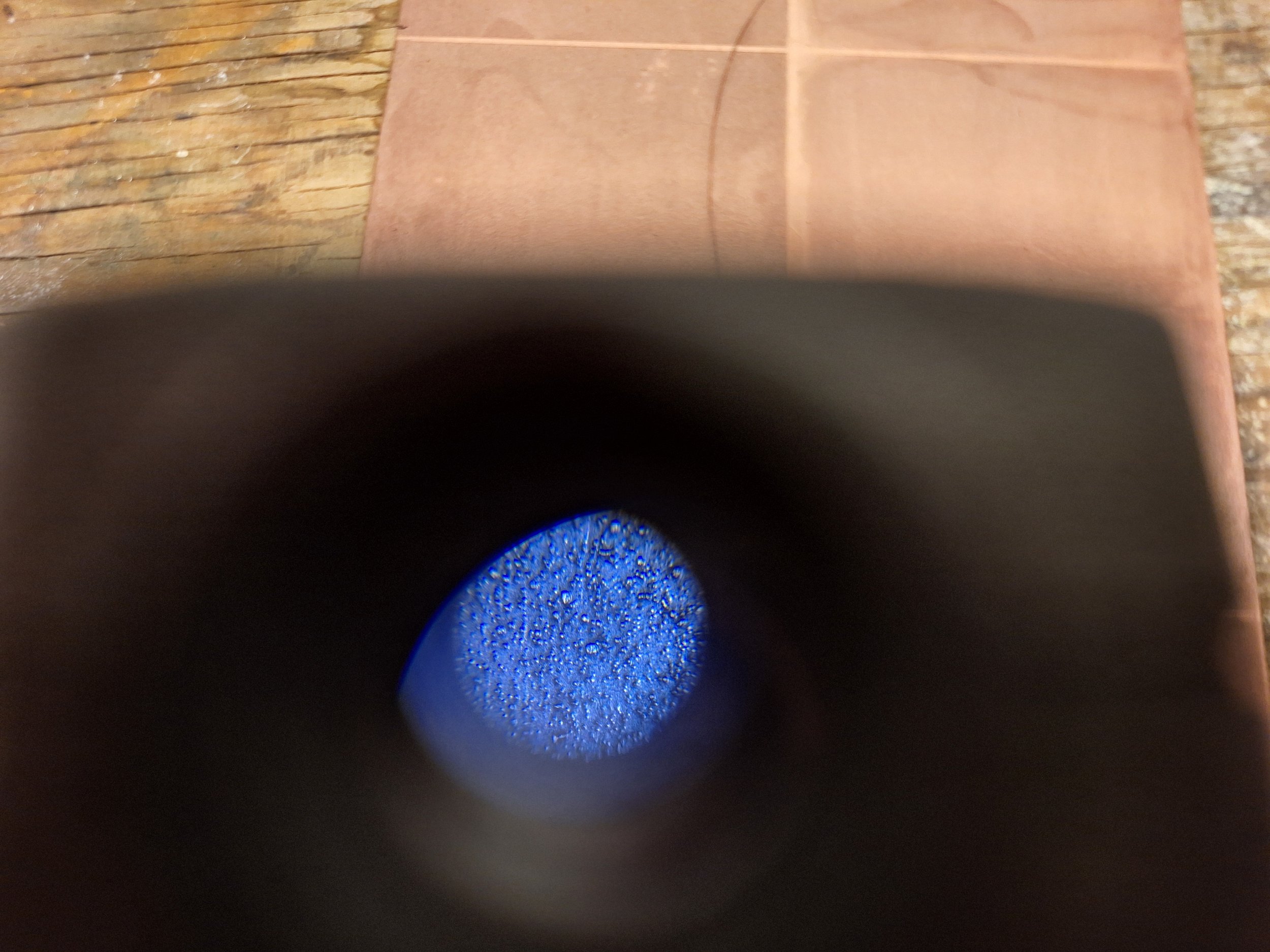

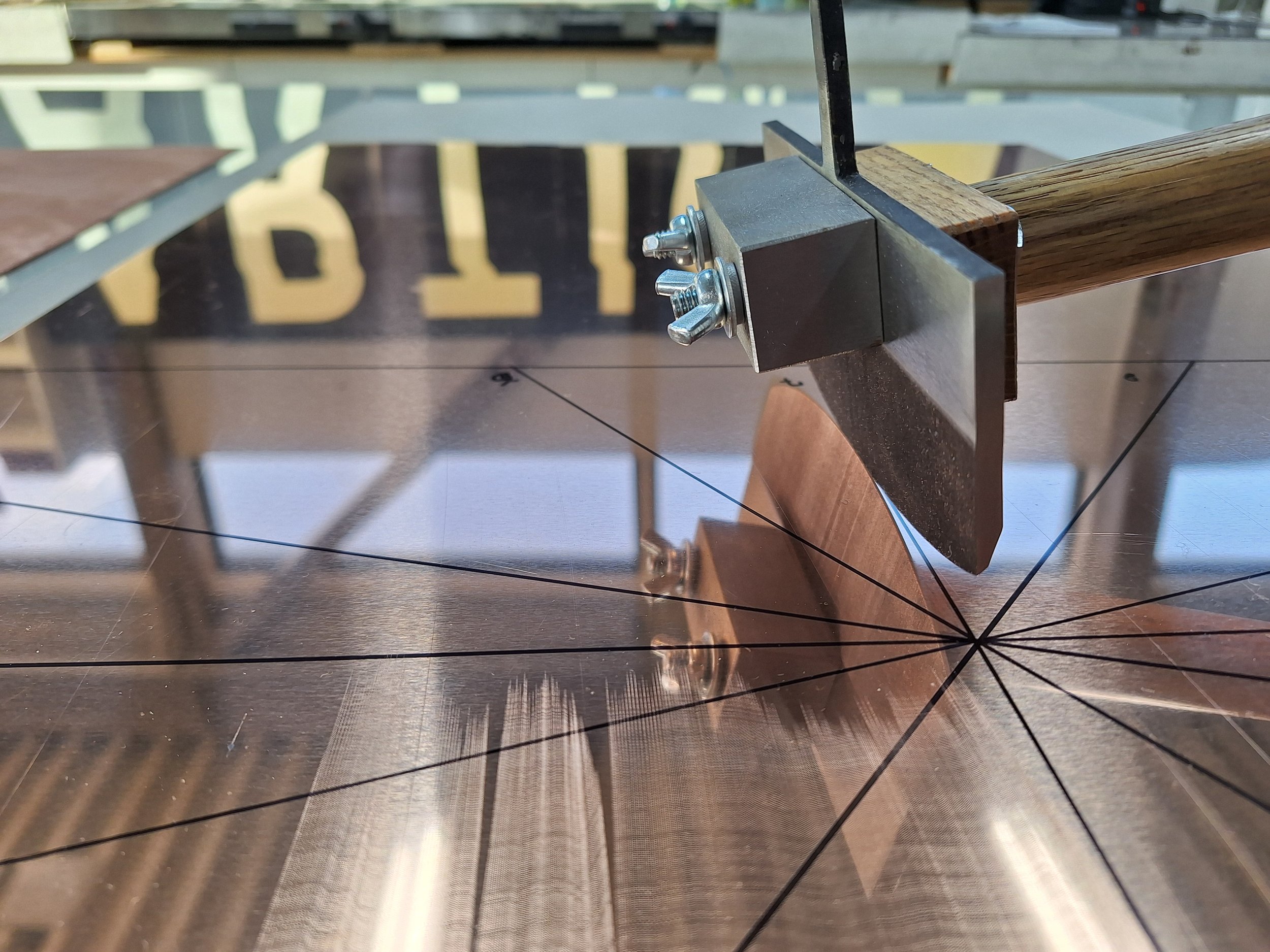

After spending much of last week in the print studio conducting boring, but necessary aquatint step etching tests, I finally managed to produce some good printing results. Every workshop has a slightly different setup, and variations in climate, acid strengths, printing felts, papers etc. means that I cannot always operate with the same measurements, ratios and times that would render me pristine prints at home. I was getting some rather disheartening results at first - however, I managed to identify the problems after a lot of trial and error, trying to eliminate whether my issues were related to my aquatinting, etching or printing processes. Having finally cracked the code, I am excited to embark on the fun stuff next week (i.e. actually producing art). I have also spent a lot of time rocking mezzotint plates, grounding up the copper surface so that I can scrape and polish down images. All the while consuming copious amounts of audiobooks.

Gruve 3 (mine 3)

In between studio hours I have been conducting quite a bit of research on Svalbard, and to kick off Easter week I went on a guided tour around Gruve 3 (Mine 3), which is located just north of Longyearbyen. Longyearbyen, and modern human presence at Svalbard, owes its existence to the local coal mining industry. Longyearbyen (Longyear City) was named after American businessman John Munro Longyear, who started the Arctic Coal Company here in 1906. The Norwegian Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani (SNSK) took over in 1916, and is still responsible for operating the last open mine, Gruve 7. As mentioned in my previous post, Gruve 7 will be closing next year, and thus ending an era of Svalbard history.

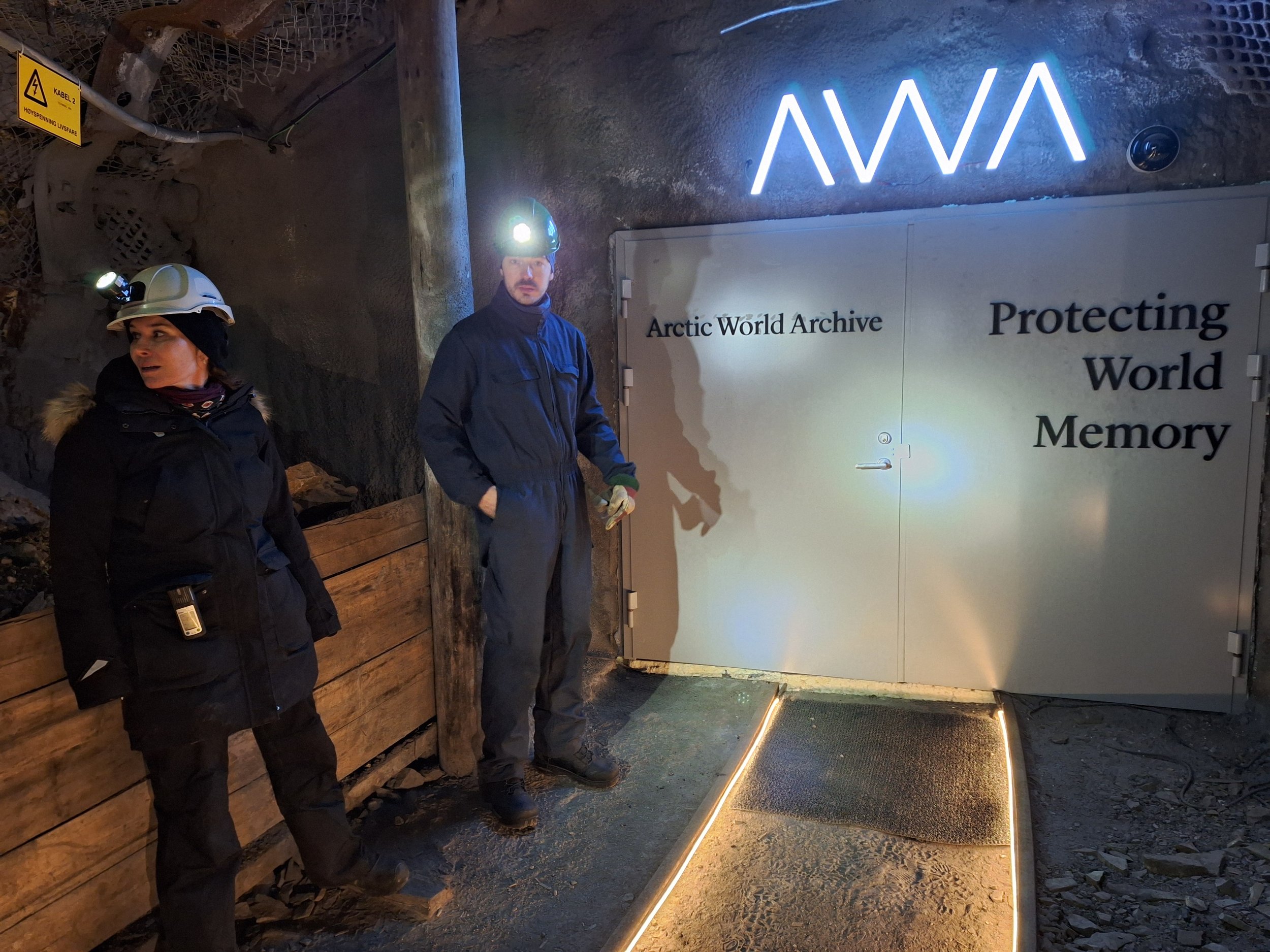

Before entering the mines, we were equipped with authentic coveralls and helmets with a headlight. Before the tour, we also watched a short film shot in Gruve 3 by NRK in 1985, which gave a good sense of the working conditions of the miners. The tour exceeded all expectations - the history of Svalbard’s coal industry proved incredibly interesting, and the tour guide was very engaging. I never thought I would enjoy touring dark dusty tunnels as much as I did.

What heightened the experience of Gruve 3 was how it had become a slightly eerie, but well preserved time capsule. In the middle of their shift on 1 November 1996, the miners were told to pack up, as they were being moved to work in another local mine. Everything sits exactly as they left it that day - the cheese stored in the underground pantry, the magazines in the mining carts and the pin-up ladies on the walls. (As you can imagine, this was a very male-dominated workplace, although women did find their way into the mines eventually).

Arctic World Archive (AWA)

Not just being an accidental time capsule of the 90s, Gruve 3 has also become the host of The Arctic World Archive (AWA). Cutting deep into the permafrost like its neighboring Global Seed Vault, AWA opened in 2017 as a space to store our world heritage. SNSK is responsible for the operation and maintenance of the vault, including security and access control. On their website, AWA is described as a “secure underground and unhackable data vault at the centre of the permafrost, 300 metres inside the mine and 300 metres below the top of the mountain”. Digital files are stored in a piqlFilm, which is a “migration free, future proof and passive storage technology with a very low CO2 footprint that is extremely cost efficient and sustainable over time. The technology needs no servers, no migration, no electricity to keep the data alive for centuries.” Like the Global Seed Vault protects our future food supply and gene banks, AWA safeguards our digital and cultural legacy. Once again, past and future connects at Svalbard - both physically and metaphorically.

Migrant Ecologies Project

What does Svalbard and Singapore have in common? Ever since getting this residency, I have been asking myself that very question. How can I interpret my new surroundings through the lense of my Norwegian-Singaporean heritage and artistic research on diasporic memory? How can I create a bridge between a tropical island near the equator and an icy archipelago above the arctic circle?

Turns out, there is very special grain of wheat which lies buried behind this door inside Gruve 3:

Text taken from https://migrantecologies.org/Natural-Histories-Seeding-Stories:

On 10 June 2019, a single grain of wheat from the interior of a 133-year-dead, 4.7 metres long, saltwater crocodile shot in 1887 at the mouth of the no-longer-existing Serangoon River in Singapore and kept for over a century in the Raffles Museum, migrated to the Arctic circle. Migrant Ecologies Project artist Zachary Chan was flown to Svalbard with this very special grain of wheat and a series of other artistic offerings from the Migrant Ecologies Project for a ceremony, in which the works were offered to the mountain and placed to rest in Gruve/Mine 3, next to the Svalbard Global Seed Bank.

Our proposal consisted of regarding this 133-year-dead, saltwater crocodile as a comparative seed bank to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. But equally important for us has been the discovery of what has become a feral diversity of sources all claiming in different ways that this very crocodile is believed to host the spirit of Panglima (Warrior) Ah Chong, 19th century gangster, Taoist mystic, and anti-colonial freedom fighter.

How might such disparate beings as a wheat grain, a crocodile, and a spirit being, all entangled in the legacies of colonial agro-economies and monstrous dreams of progress, speak to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in a time of mass extinction and climate change?

Singapore and Svalbard are two islands situated in radically different parts of the globe.

There was, as we know, a violent scramble for natural resources by colonial powers from which Singapore emerged as entrepôt trading post in the 19th and 20th century. And the emergence and increase in attacks by saltwater crocodiles throughout our region can be seen as an ongoing result of the devastating impact of colonial and postcolonial capital on coastal ecosystems.

There is also a potential equivalent scramble for the Arctic commencing right now as China, Russia and America all compete for the precious minerals and sea routes that are being uncovered as the ice melts. Incursions by polar bears into the town of Longyearbyen are also on the rise.

Might Svalbard become the Singapore of the 21st century? And if so, what kind of worlds might this new entrepôt inherit?

Lots of food for thought.