I have now spent a week in Longyearbyen, and am happily settling in at ARTICA and acquainting myself with my immediate surroundings. (As polar bears roam these islands, I am not allowed to leave the settlements without an armed guide). Everyone has been so welcoming and friendly, and it has been great being introduced to fellow residents and creatives during my first few days here. I honestly feel as if I have been here for a month already.

delving into the svalbard archives

This week, thanks to the help of residence coordinator Lisa, my fellow resident Ellen and I got to visit the archives of Svalbard Museum together with Head of Collections Ann Kristin Klausen and conservator Unn Gelting. They graciously lead us behind the scenes to share with us the many fascinating objects in their magazines, as well as telling us about their ongoing conservation work. With the permafrost rapidly thawing, a lot of graves of early 17th-18th century Dutch whale hunters are being exposed or are in danger of being washed out to sea. Several well preserved textiles and clothing items have thus been excavated from the ice, as well as items from early fur trappers’ huts. (That being said, objects from more recent excavations have deteriorated a lot more due to melting ice).

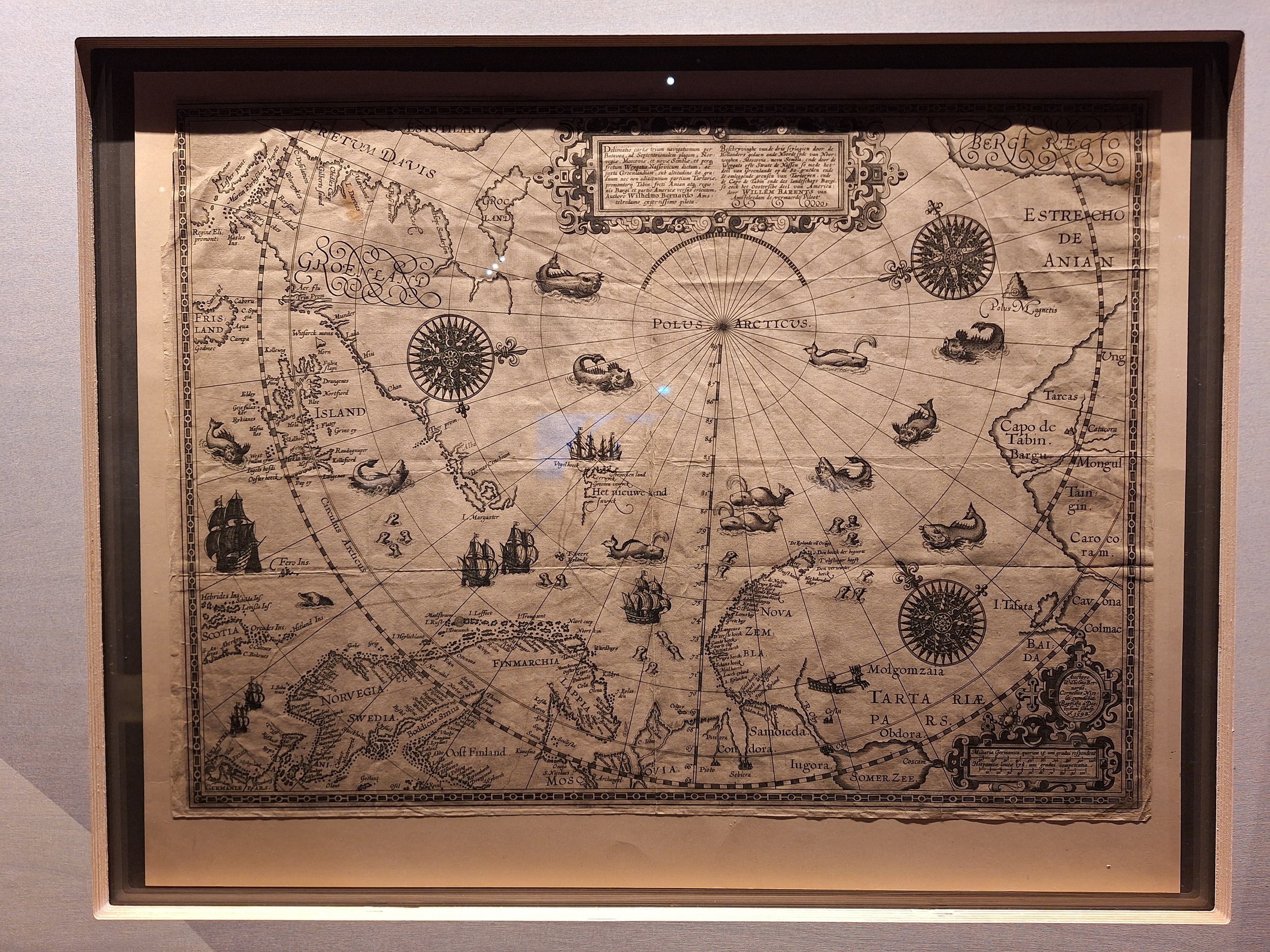

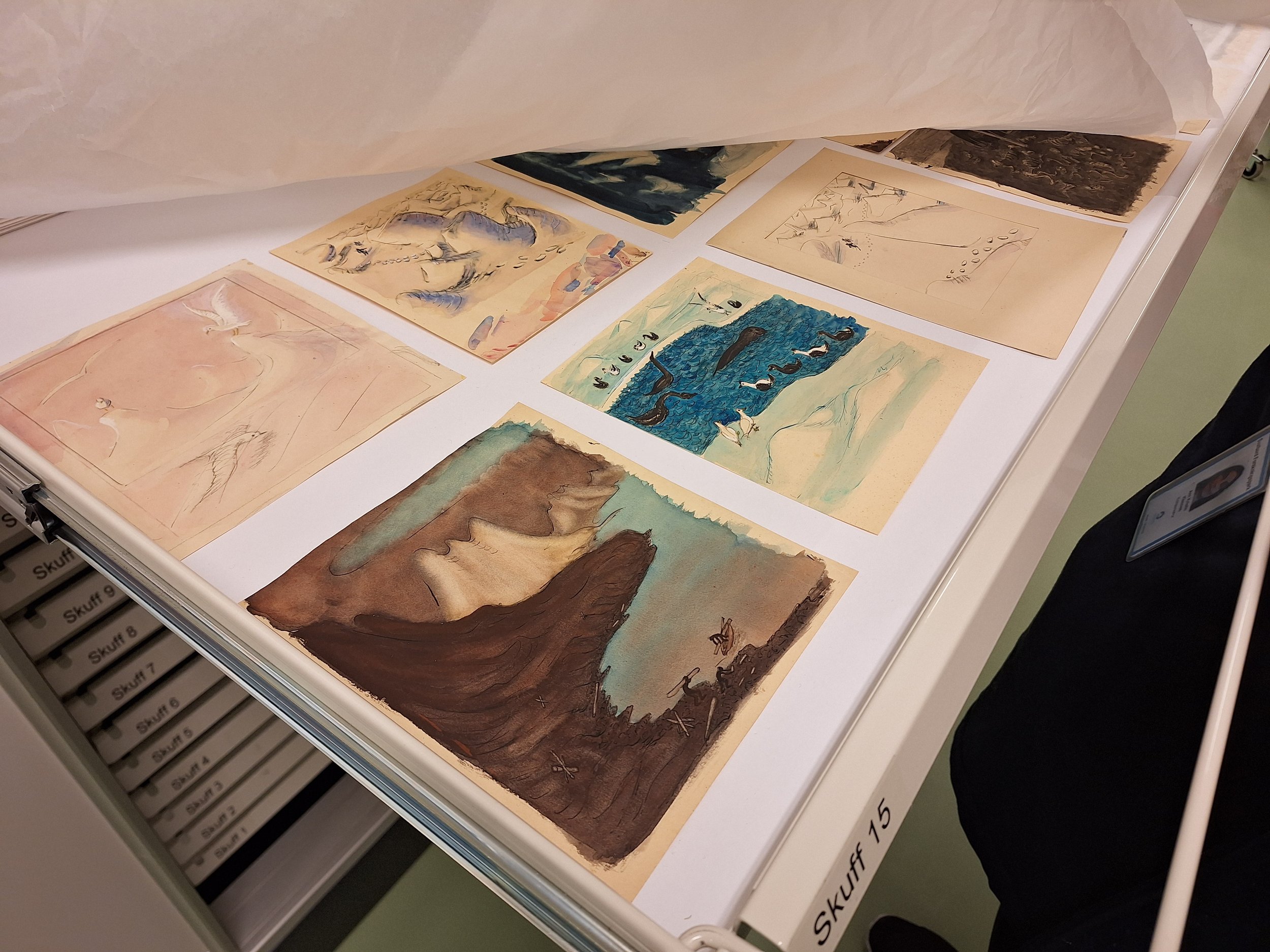

As a printmaker, I was also very interested in looking at early maps of Svalbard and early depictions of the Arctic by the first explorers. The oldest and most famous map is the Barentsz Map from 1598. It is on display in the museum’s permanent collection, and shows the first ever depiction of Svalbard, here simply indicated as "Het Nieuwe Land" (Dutch for "the New Land"). The museum archive also holds a vast collection of Svalbard watercolours from the 1930s by Austrian traveller Christiane Ritter.

coal mines and the global seed vault

It is impossible to come to Svalbard and not feel that it is going to influence you in some ways. I came here as an artist with my own artistic concepts and plans in mind, but from the first day I realised that I cannot escape incorporating Svalbard into my work in one way or another. This place possesses too much of a strong mental and physical presence for it to be avoidable. How can I tie my stories to those of Svalbard, and how might this be manifested in the artworks I produce here?

Naturally, many artists are drawn to the nature, and many also touch directly upon themes relating to climate change and its consequences. In my own work, I muse on topics surrounding family histories, diaspora and nostalgia - nostalgia for pasts we never experienced, and nostalgia for futures that never even manifested themselves. What immediately struck me about this place is that it seems to operate with a different sense of time. It is a place where past and future are constantly juggled, and they loom over the present like ghosts. Longyearbyen was built in 1906 as a consequence of the rising coal mining industry, and remnants of this past can still be found all around, like an alternative steam punk reality. However, this link to the past is a chapter about to be closed when the last mine (Gruve 7) shuts down next year. The coal reserves are being exhausted, the remaining coal is of a lesser quality, and the industry no longer aligns with contemporary visions of a greener future.

In the place of coal miners now flock scientists and researchers from all over the world, deeply concerned with how the Arctic is losing its memory, and vigorously collecting ice samples and geological specimens in a desperate measure to counteract the collective loss we are facing with the melting landscape. No place on earth are the consequences of climate change felt more strongly than here, and in a way this place is the very symbol of a dying future. Simultaneously, and ironically, Svalbard has become the place in which humanity shall depend for its survival. The Global Seed Vault outside Longyearbyen cuts 130 meters into the permafrost, and serves as a back up for 1.3 million of the worlds seeds - providing security for the world’s future food supply and gene banks from natural disasters, climate change, disease and wars. Fittingly nicknamed “The Doomsday Vault”, it is both a beautiful and terrifying concept.

Talking to people who live or have lived in Svalbard, this archipelago does not really have a shared collective history of a people who has witnessed it for generations. The Svalbard community is diasporic in many ways - people from all over the world only live here for a certain amount of time before they have to leave. You cannot be born here. You cannot die and be buried here. Scattered around the globe, the people who have lived in Svalbard are tied together by their memories and experiences of the place. However, everyone’s idea of it is set in a certain time. I see some clear parallels to the Chinese diaspora which I am familiar with in my own Chinese-Singaporean family - everyone’s idea of Singapore is stuck in the time in which it was left. And we, the ancestors, are somehow carrying the mythological idea of the “homeland” with us, even though we never experienced it ourselves. At the same time, we keep wondering what an alternative future would have been like - a future in which the homeland had never been left. Svalbard seems to me the place where futures come to live and die. Nostalgia for the past and future feel almost stronger than the present. I am hoping this might prove an interesting link and entryway for me to explore over the next three months.